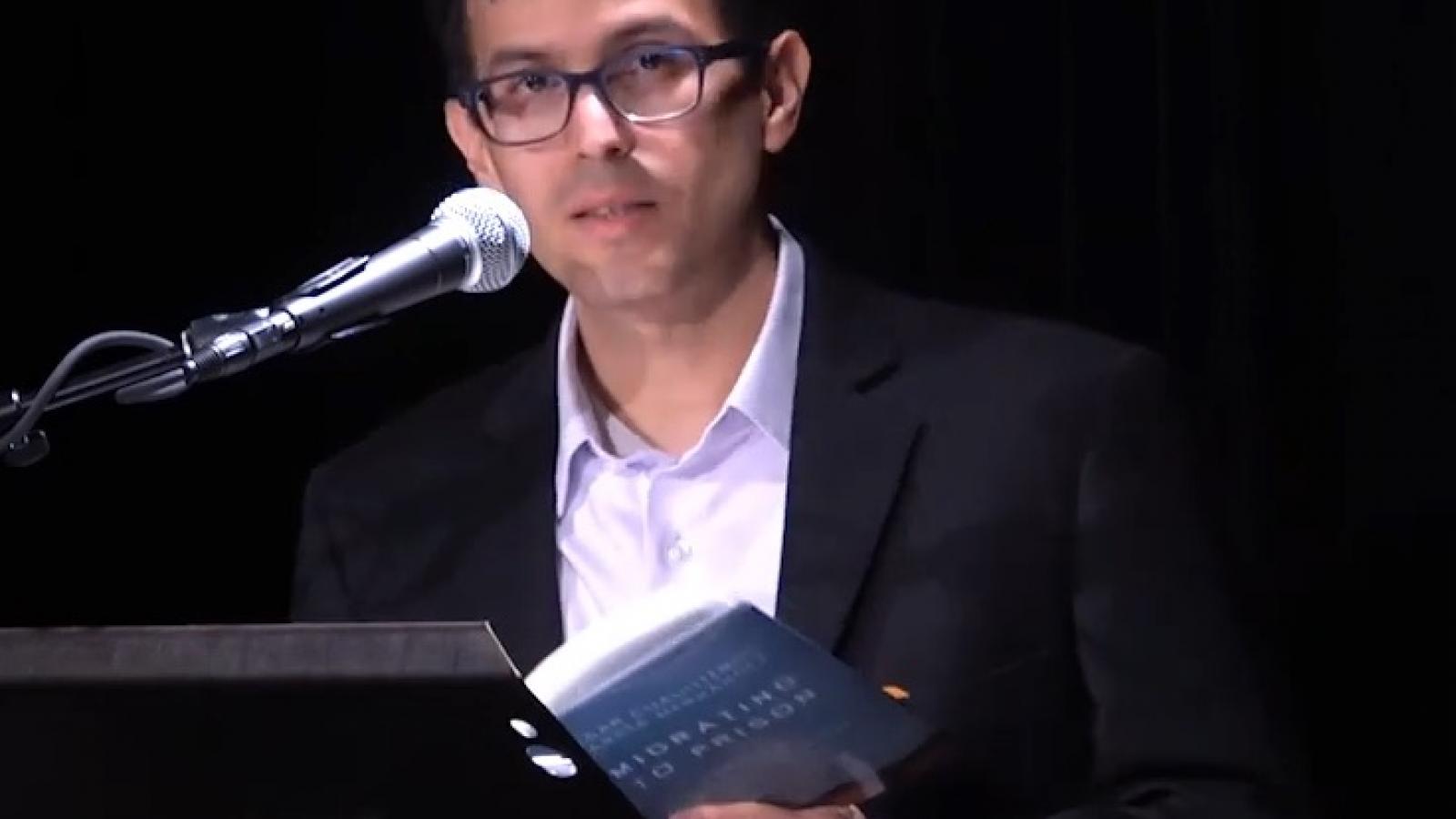

Faculty Spotlight: César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández

César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández joins the Moritz College of Law at OSU as the Gregory Williams Chair in Civil Rights & Civil Liberties in August 2021. He has published extensively about the criminalization of immigration under U.S. law, and blogs at crimmigation.com.

Your most recent book is entitled Migrating to Prison: America’s Obsession with Locking Up Immigrants. What motivated you to write the book and what's the main takeaway point from it?

Under President Obama, the United States government detained hundreds of thousands of migrants every year as immigration officials decided if they would be allowed to remain in the country. As a lawyer representing many people in this situation, I heard complaints about physical abuse and sexual assaults, but outside the walls of immigration prisons few people paid attention. Migrating to Prison came out when President Trump occupied the White House, but I wrote it because of what happened under President Obama, practices and policies which became more severe under Trump. The book revolves around the growth of immigration prisons. Importantly, growth implies a beginning: imprisonment wasn’t always used to enforce immigration law like it is now. For decades in the not-too-distant past, immigration law enforcement looked much different. I hope readers focus on the fact that how we do things now wasn’t inevitable. Key decisions at key moments led to the immigration prison practice that currently exists. If the country is to follow a different path in the future, it will likewise come about one decision at a time.

Your book has an epigraph from James Baldwin (“in our time, as in every time, the impossible is the least that one can demand”). Why did you choose that quotation, and what does it mean to you?

I’ve been writing about abolishing immigration prisons since 2017 and talking to diverse audiences about this for many more years. People often focus on the impossibility of shutting down a vast prison network. To me, there is no one who urges people to think imaginatively—indeed, to dream—about the future more powerfully than the life example and poetic prose of James Baldwin.

Your work forms part of a much broader “abolitionist” movement challenging the system of mass incarceration in the US. How do you see the long-term prospects for that movement, and what are its more immediate goals?

Since I published Migrating to Prison, racial justice movements have made an immense leap. Ideas that were once unknown to most people have become part of everyday conversations and activism has become a feature of life for many others. I don’t know whether the United States will abolish immigration prisons or prisons of any kind while I’m alive—or, frankly, ever. But I can say that abolition has become a central topic of conversation in the last few years. For me, that’s a sign of the movement’s success and power. What comes next will depend on the efforts of organizers, artists, intellectuals, legislators, and all the rest of us in identifying the world we want to live in, then setting about building it.

What’s your perspective on the Biden administration's actions on immigration policy so far? Does their approach to immigration signal any kind of break with Trump’s (or even Obama’s) policies?

Five months in, the Biden administration has sent mixed signals when it comes to immigration policy. From the President on down there has been a sharp break from the Trump administration’s racist rhetoric. When it comes to substantive policy, the Biden administration has rolled back several initiatives that epitomized the Trump administration’s approach to migrants. For example, under President Biden, federal officials have launched an effort to reunite parents separated from their children while also ending the Trump administration’s Migrant Protection Protocols (commonly known as the Remain in Mexico initiative) that blocked asylum applicants from entering the United States. These are meaningful shifts in the federal government’s tone and substance that should not be minimized. That said, the Biden administration hasn’t used all the levers in its control to improve conditions for migrants. For example, the first batch of immigration judges appointed by Biden’s attorney general, Merrick Garland, were vetted under Trump. Meanwhile, the number of migrants detained by the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency has grown since Biden took office.

You grew up in South Texas in the 1980’s, witnessing the arrival of tens of thousands of Central Americans fleeing the political conflicts and proxy wars being fought in their countries. Can you talk about how that experience shaped your awareness and desire to work in immigration law?

I am certainly a child of the 1980s borderlands where South Texas meets northeastern México. This was the vantage point from which I first experienced the brute power of the law in the form of Border Patrol officials who breathed fear into the lives of many adults in my community. As a child, I didn’t have a sophisticated understanding, but I knew that an agent in green uniform could sometimes mean an adult’s inability to live with their family. That foundational exposure to policing and the awesome power of discretionary law enforcement shaped my life. Professionally, I’ve tried to make sense of how policing operates and why. Personally, I’ve tried to insulate myself from policing’s adverse impacts. This region is much different now than when I was born and raised there, but it’s still the place I return to time and again (indeed, I wrote these words from my mom’s house in McAllen, Texas).

You’re coming to Ohio State from the University of Denver, where you were part of the Rocky Mountain Collective on Race, Place and the Law. What makes Ohio/the Midwest a good place for the kind of work you want to do? How do you see this work shaping the Williams Chair on Civil Rights and Civil Liberties?

I couldn’t be more excited about joining Ohio State and that’s largely because of its people. This is a university with an impressive record of fostering creative thinking across many disciplines. From students to faculty, I have found this to be an intellectually engaged and sophisticated community of imaginative thinkers. In many ways, it’s a large, multidisciplinary version of the Rocky Mountain Collective on Race, Place and Law that I was fortunate to be part of at the University of Denver. As a researcher and teacher who enjoys engaging with a wide variety of audiences, Ohio State’s breadth of expertise promises to push me like never. That’s a challenge I couldn’t turn down. I carry the title of the Williams Chair in Civil Rights and Civil Liberties with humility knowing very well the remarkable scholars who have held this position before me. In part, my goal is to incorporate migration studies more squarely into the rich tradition of teaching and research about civil rights and civil liberties at Ohio State.

The Center for Ethnic Studies at OSU is still young and your arrival to campus will be a welcome addition to this group. At the same time, Ethnic Studies has been the target of bans and other attacks. What do you think is the role of Ethnic Studies within the university and Ohio/the Midwest given this context?

In an imperfect political community like ours, past struggles and present-day contests over the rightful place many of us occupy in the arts, business, the courts, culture, politics, and on the streets set the tone for the direction that the future of the United States takes. Understanding how race and ethnicity fit into our nation’s past and present is key to shaping its future. Ethnic studies as a disciplinary tradition is vital to that development. As a vibrant intellectual community tasked with training future generations of leaders, it’s essential that OSU engage seriously and rigorously with the heartaches of the past, the challenges of the present, and the possibilities of the future.